The power of the pause – wherever you are, be there!

Brian is a senior leader who requested coaching following his recent promotion. Previously always seen as a high performer in his leadership positions, he had recently received feedback from his manager to develop a more collaborative and engaging style and to be less aggressive.

This was our first face-to-face meeting, where we were discussing his outcomes for his 1-2-1 coaching programme. “Look, this is what I am up against,” Brian sighed as he handed me a sheet of paper, a printed copy of his business diary for the next week. “How can I spend time with my team when I just do not have time to breathe anymore?”

Looking down at his calendar, day after day was filled with meeting after meeting; one after another with an occasional lunch. Brian said his work agenda felt like a runaway train that he just could not stop, and he did not know what this was all for anymore.

He was aware that he over-reacted with his team members when project milestones had not been met, but he could not stop his anger boiling over. I was experiencing his state as “frazzled,” a term described by Dan Goleman and used in neuroscience to define a constant stressed state that overwhelms the nervous system with neurochemicals such as the stress hormone cortisol (each hit of cortisol staying in the system for 10 hours).

Being in this state means the mind is often ruminating with worries about work, and this becomes a reactive loop preparing the nervous system to respond to any slight trigger. This emotional exhaustion can often lead to burnout.

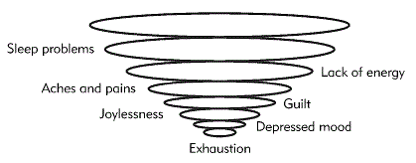

In their book, ‘Finding Peace in a Frantic World,’ Mark Williams and Danny Penman introduce the concept of the ‘Exhaustion Funnel,’ developed by Professor Marie Asberg (see diagram below). This provided a good way to look at Brian’s situation.

The circle at the top describes how things are when we are living a full and balanced life. As work pressures increased and things got busier, Brian started to give things up to focus on work and the pressures and stressors he was experiencing.

The narrowing circles in the diagram represent the narrowing of life. As the pressures mounted and the stress continued, Brian would give up more and more, and the circles would then continue to narrow.

Often the first things that we give up are the things in our life that seem optional but are often the ones that most nourish us.

In our sessions, Brian spoke about the fact he no longer could find the time to go to the gym and pursue his hobbies such as rugby; his time with his friends and family were now also being impacted.

If this continued, the result might be that Brian would be left solely with work and the work stressors that were depleting him further. Without the areas in his life that he finds resourcing and nourishing, the result is exhaustion and burnout.

Professor Marie Asberg (from the Karolinska Insitute, and an expert in burnout) identified that those of us who continue downward furthest are likely to be those:

- Who are most conscientious

- Whose level of self-confidence is closely dependent on their performance at work.

This funnel depicted Brian’s experience since his promotion; being someone that had been identified as a high performer early on in his leadership career and taking part in numerous talent programmes had resulted in rapid progression.

Now in his mid-thirties, Brian was starting to experience the shadow of his achievement drive and the constant doing meant he had little time during the working day for anything else. His strategies and resources that he had previously used to counterbalance the effects of stress were now less effective or being depleted.

In addition, Brian’s constant activity, meeting agenda and the amount of information he was dealing with was continually diminishing his ability to make effective decisions and regulate his impulse control – so when he needed to interact with his team, he was continually reacting from a cycle of stress rather then consciously responding to what his team needed of him.

Before we worked on Brian’s leadership style and impact, we first needed to build up his levels of energy and resourcefulness. We explored a number of interventions to help Brian recalibrate his sleep hygiene and work life integration – developing a mindfulness practice was one which was critical for him to use to develop a more presence-based leadership mode of mind.

Tara Brach describes mindfulness as “the intentional process of paying attention, without judgment, to the unfolding of moment-by-moment experience.”

Over this last decade, there has been much written about the scientifically-researched psychological and physiological benefits of developing a regular mindfulness practise. For senior leaders that are dealing with daily stressors within their roles, developing a way to manage the effects of the fight and flight response is paramount in order to ensure they perform over time without being worn down and worn out.

In an interview with Herbert Benson, MD and Associate Professor at Harvard, Judith Ross, highlights the importance of a fifteen to twenty minute mindfulness practice to counter the effects of daily stress.

Benson calls these practices a ‘relaxation response,’ a physical state of rest, which acts as an antidote to the fight and flight response; this is key to maintaining our performance when under pressure.

The relaxation response is elicited by breaking the train of everyday thought. It counteracts the fight-or-flight response, decreasing metabolism, slowing heart rate and breathing, and lowering blood pressure. In fact, Benson’s most recent research shows that eliciting the relaxation response can bring about physiological changes that offset the harmful effects of stress.

Once Brian had developed a regular ‘relaxation response’ through mindfulness practice, a stable foundation, we then worked on how he could bring a more mindful mode of mind into his daily work; he did this through consciously pausing.

As Saki Santorelli describes, ‘the willingness to stop and be present leads to seeing and relating to circumstances and events with more clarity and directness. Out of this directness seems to emerge deeper understanding or insight into the life unfolding within and before us.

Such insight allows us the possibility of choosing responses most called for by the situation rather than those reactively driven by fear, habit or long-standing training.”

A key study by Daniel Gilbert and Matthew Killingsworth reported we spend a large part of our waking hours (around 47%) mind wandering on autopilot; this often results in dulling our experience as we are not aware of what we are experiencing as we experience it.

More importantly, this study concluded that when we are in a state of mind wandering, we are often ruminating about events that have happened in the past or future events (usually around 50% of the time). It is this for this reason that neuroscientists say, “wandering minds are unhappy minds!”

In these moments, when we are lost in our negative thoughts our ‘buttons’ often get pushed and we start to react before we are consciously aware of it. For leaders like Brian, especially in a constant state of stress, this is when they are likely to over-react! So developing a habit of pausing during the day provided Brian with the opportunity of waking up from autopilot and developing a more conscious way of leading.

“Do you make regular visits to yourself?” – Rumi

Through learning to pause, Brian developed a deeper self-awareness of his patterns of emotional reactivity and learned to read his physical symptoms of stress more and more. If he noticed he was in a reactive state, he would consciously choose to practice a mindfulness exercise he had learnt.

These moments of pausing before interactions with his team meant Brian was not carrying stressors over into these interpersonal situations. As he was in a more neutral state, he was able to attune more to their specific needs and his team started to experience a more empathic style.

Pausing also provided Brian with a conscious space to disconnect from the constant stimulus he was facing throughout the day and as a result he developed a greater awareness of his relationship with social media and technology. He came to realise how each tweet he read, email he responded to and web page he reviewed all reduce his brain’s executive function.

Through pausing, Brian started to take longer and more conscious breaks throughout the day. (Research confirms optimal brain function is achieved via one hour of intensive activity followed by 15 to 20 mins of relaxed activity).

Most importantly, leaders such as Brian are working within an increasingly unstable, rapidly changing and demanding context known frequently as a “VUCA” environment. This military derived acronym was developed in the late 1990’s by Bob Johansen, standing for the

- Volatility

- Uncertainty

- Complexity, and

- Ambiguity

Learning to pause is a way to move into a more conscious mode of mind as a leader. The movement inwards enables us to come back to ourselves when frequently our autopilot mode of being is actually moving us further away from the present moment (with agitated thoughts and worries about the future or the past).

For Brian, over time, pausing helped him to connect more regularly to his core sense of authenticity (his inner compass) and resourcefulness. It built on the foundations of his regular mindfulness practice to enable him to find what Frankl describes as the space in between stimulus and response.

“Between the stimulus and the response there is a space and in that space lies our power and our freedom.” – Viktor Frankl

To help leaders such as Brian develop a process of pausing regularly each day, my colleague Karyn Prentice and I developed the following pneumonic to support the internal and external movements of awareness in this practise:

P – PRESENT

A – ALLOW

U – UNPLUG

S – SENSE

E – EMBODY

Why not give this practise a go right now by following these guiding principles for a pause:

1. Present – Change your posture by sitting or standing upright, to signal you are waking up from autopilot and to embody alertness. Take three conscious breaths as a way of taking an inner time out from the momentum of your day.

2. Allow – Allow your experience to be just as it is, without trying to change it or wishing it to be different. Be fully awake and aware of what you are experiencing – ask yourself, what am I experiencing in my mind, emotions and body?

3. Unplug – Let things be just as they are. Take a step back and observe how you are relating to your experience without any judgement.

4. Sense – Tune into your senses – sight (you might notice 5 things about the place you are in), hearing, smell, taste and touch. Use your sensory information as a way of bringing you into this present moment. Be aware of the physical sensations of standing or sitting – the weight of the body going into the ground.

5. Embody – Now consciously choose to take this present moment and grounded awareness into the next moments of your day.

Now think about the core transition points in your working day; examples might include:

- arriving in the office

- having a coffee

- having lunch

- before or after a critical meeting

- going home.

Try building in a pause a number of times in your day as a way of resetting and reconnecting with yourself, your work, the decisions you are making and the way you are responding to your team.

As with any new habit the key thing is to practise, so repetition and reinforcement are key. Personally, I have a reminder that sounds on my phone every hour to remind me to seek refuge and take a pause – why not try it for a week and see the impact it has on you, your work and the people in your life?

“Learning to pause is the first step in the practice of Radical Acceptance. A pause is a suspension of activity, a time of temporary disengagement when we are no longer moving toward any goal…The pause can occur in the midst of almost any activity and can last for an instant, for hours or for seasons of our life….you might try it now: Stop reading and sit there, doing “no thing,” and simply notice what you are experiencing.” – Tara Brach

More mindfulness resources

For more mindfulness resources, including free guided sessions via MP3 and top tips on how to develop a mindfulness practice, make sure you join the Catalyst 14 mailing list.

References:

- Focus – Dan Goleman

- Mindfulness, Finding Peace in a Frantic World – Mark Williams and Danny Penman.

- How to Manage your Stress Levels – Judith Ross, Harvard Business Review.

- Heal Thy Self – Saki Santorelli

- A wandering mind is an unhappy mind – Matthew Killingsworth and Daniel Gilbert

- Radical Acceptance – Tara Brach.

Get free coaching and mindfulness resources

Join our community for free and get a host of free resources, including our guide to becoming a professional coach, access to our coaching webinars, a free mindfulness e-kit and much more.